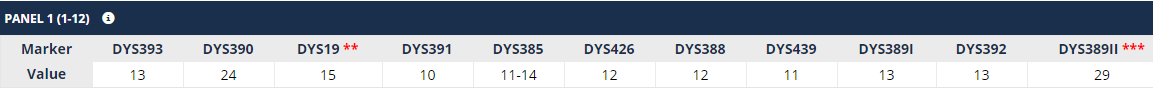

Once you receive the email that your results are in, use the supplied link to login to your FTDNA Personal Page. Next scroll down to the Y-DNA section and click the the Y-DNA Results link.

You should see something link the image below. This shows what the results of the first 12 markers of a typical Albemarle Davenport might look like. Of course, your results may vary. The top row of numbers is the marker name – DYS 393, DYS 390, etc, while the second row is the actual value for the marker.

Comparisons are important. On their own, these numbers are not very helpful, but they gain their usefulness when compared to others. Each Davenport line has its own signature, or Haplotype. The Pamunkey Haplogroup is different than the Newbury Haplotype, which is different than the Rev John Haplotype, and so on.

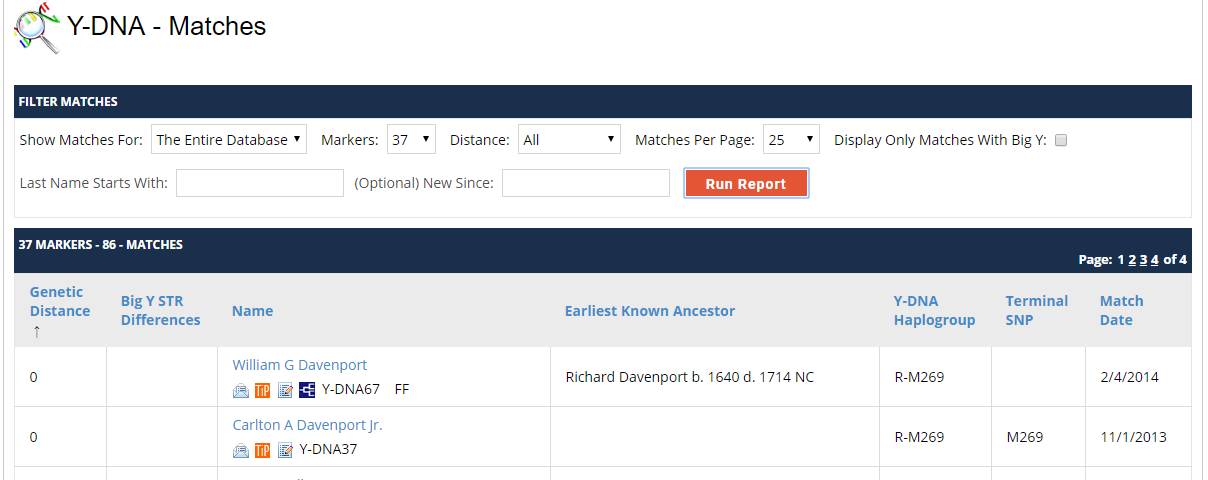

Now go back to the Y-DNA Section and click on Matches. You should now see something like the image below. It is a list of other participants that match you at the various testing levels – 12, 25, 37 markers, etc…. If there is a good match at 37 markers or more, and the other person is named Davenport, then you have found a home. If it is not a Davenport, more research is required.

Ideally, all male Davenports in the line would have identical Y-DNA. However, stuff happens. During the replication process a piece of the DNA might be deleted or inserted into one of the marker locations. What was, for our purposes, a value of 24 might now become be a 23 or 25. This "mutation" is rare, random and harmless. If you followed the progress of one marker over a 12 to 15 generations, we might see one, two, or maybe no mutations. We try to test as many markers as possible, because this gives us more mutation "opportunities" to look at and compare. Some markers mutate faster than others,but once a mutation occurs, it is passed onto all future generations. This is a good thing. It enables us to use Y-DNA to distinguish the different Davenport lines and sometimes the branches within.

When comparing individuals, you must compare all the markers available. You can’t just ignore the markers that don’t match and favor the markers that do. For 37 markers, two people would match if 33 or more of the 37 markers matched exactly. This number is not set in stone, because if their suspected common ancestor was several hundred years away, then it is a number we would expect. An exact 37/37 match would usually be more closely related than 33/37. Remember, mutations are rare. The 33/37 match would have needed more generations, or mutation opportunities, to allow those 4 mutations to occur. If there was a 30/37 match with seven markers just being 1 off, it doesn’t matter. There just isn’t enough time for 7 markers to mutate within a useful genealogical time frame.

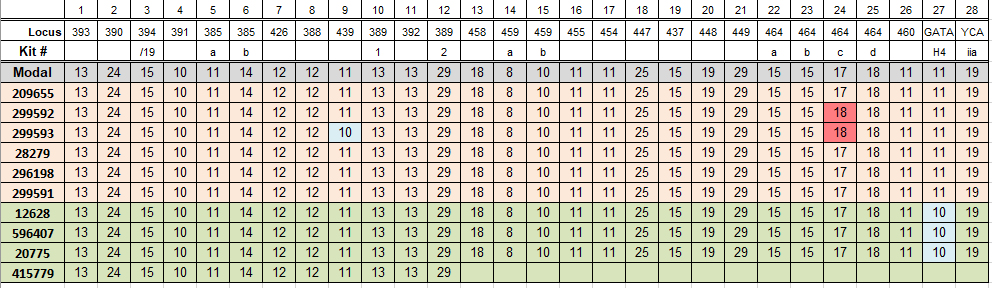

The next diagram, from the DavenportDNA website, shows results of the first 28 markers for several members of the Albemarle line. Two rows have been added. The top number is just the placement of the marker in the list – no. 3 is the 3rd marker. It just makes it easier to refer to it. This sequence is mostly based on the order the marker was originally discovered on the Y-Chromosome. The “Modal” row is the value of each marker, we believe, the original (Richard) Davenport had, based on the current values of his descendants results. So, the idea is to compare each sample to the modal, not each other. If the sample value is lower than the modal, then that cell will have a blue shade to it. If it is higher, then it will have a red shade. But, in reality, we don’t care which way it goes. It is the number of mismatches that counts.

Normally, the samples are placed in order by what is known in the paper genealogy, oldest to youngest within the family line. When that is not known, it is placed nearest to the sample with the closest Y-DNA match.

Finding the Modal. How do we know what the modal Y-DNA looked like 10 or more generations ago? Since the Y-DNA is passed down virtually unchanged, we test a known documented descendant. At that point we have a pretty good idea what it looks like. If the progenitor or original Davenport in the line had multiple sons, we test the descendants of those sons. If they match, then we know what the modal or original Y-DNA looked like. If Son1 and Son2 had identical matches, and Son3 has one marker that was different, then we know that somewhere down Son3’s line, there was a mutation. It is important to remember, that the Y-DNA test cannot pinpoint a specific male Davenport. After all, its usefulness is finding matches. A living male Davenport should match his brothers, sons, father, Davenport uncles, male Davenport cousins, paternal grandfather, grandfather’s brothers, etc…. This also means it is not necessary to test other males in the family, because it likely will be the same and thus a waste of money.